In this modern age of nature disconnect, can a ritual lamenting extinct animals and lost habitats help people cope with environmental devastation?

This article is reproduced with the author’s permission from Undark magazine, where it was published in April 2018

AN OVERSIZED PAPER MÂCHÉ sunflower rose like a pale moon against the dusk of a central Brighton park. Amid the shivering group of 30 people on the chilly south coast of England, a funereal gong sounded. Several faces were hidden behind self-made bat masks in black and pink. Some wore construction paper bat ears. One woman sported a set of massive fine-mesh bee spectacles like cartoon aviator goggles. They were all there to participate in a mourning ceremony for the Remembrance Day for Lost Species (RDLS).

I stood among them, maskless and foot-cold, unable to decide whether this was wonderful or absurd. In the grand scheme of conservation, what difference could a ritual for pollinators held in a narrow park between two busy Brighton streets make?

According to a 2016 United Nations-sponsored study, 40 percent of invertebrate pollinator species (bees and butterflies) and 16 percent of vertebrate pollinators (bats and birds) are currently threatened with extinction. As pollinators are increasingly endangered due to habitat loss and pesticides, so too are the plants they pollinate — including an estimated one-third of global food crops that rely on insect pollination.

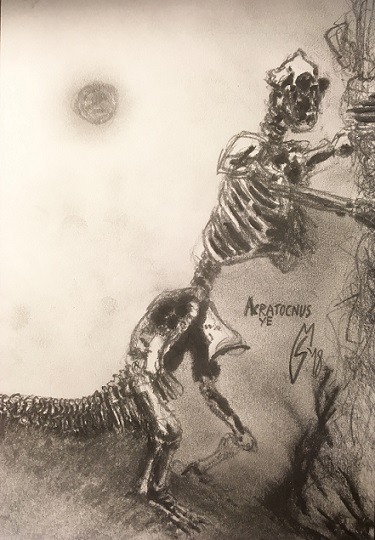

One of the unspoken aspects of extinction is that, with the exception of a few iconic animals (the passenger pigeon, the dodo), knowledge of an extinct animal all but vanishes once the species is gone. The ecosystems in which the animal or plant played its own role will alter, adapt, and depending on which species are lost, survive in one form or another. Barring dedicated research, human knowledge of that animal vanishes because often, our understanding of that species’ place in its system is nascent or non-existent when the animal goes extinct.

When Persephone Pearl, the artist at the center of the group in Brighton, viewed a taxidermic thylacine in the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery in 2010, she was deeply moved, first to tears, and then to action. The thylacine, a unique carnivorous marsupial that went extinct mainly due to hunting in Tasmania some 80 years ago, became the inspiration for a ritual that would honor the passage of creatures most people had never heard of. It’s since become something of a mascot for RDLS, which has been held annually since 2011.

RDLS is part of a growing movement that uses art and performance to confront the loss of animals and places to human development. This includes honoring endlings, a sweet word for the last survivors of species doomed to die. What I was watching, it turns out, was performance art, grieving, mourning, and community building, all wrapped into one.

Experiencing sadness at personal loss is as easy as falling down. But how do we mourn a bee or a butterfly, a bat or a bird? Talking about habitat loss is nothing new. Henry David Thoreau wasn’t just complaining about the perils of industriousness for the soul when he wrote about “shearing off those woods and making earth bald before her time.” Still, this particular kind of dramatization — dubbed ‘eco-grief’ — was something new for me. RDLS and groups like it are essentially creating outlets for coping with this sadness. The problem with denying death’s stealthy proximity is that, when it comes, we find ourselves unrehearsed.

The rituals of most religions are, by definition, for and about humanity. What we are missing is a conscious preparation for death’s possibility — not necessarily ours, but that of Earth’s other species. This is where artists can step in.

“Most of those heavily involved in RDLS have at least a partial creative background,” says Matthew Stanfield, a relative newcomer who has been closely involved with the Remembrance initiative since 2016. “Artistry has been and continues to be a big part of the initiative.” RDLS is a loose collective that invites anyone to participate; there are no blueprints other than a mutual desire for expression.

Pearl, with bright orange socks and a thick hat that did nothing to disguise her emotional focus, kept her hand on the giant sunflower as if it were a talking stick. Eyes closed, she explained the paper flower and its embellishment of dead flowers was a symbol of pollinators, of the crops that are grown with pesticides that affect pollinators; it was a stand-in for both the natural world and the world of agriculture.

Stanfield, a young man with barely tamed hair and dignified manner, had a prepared statement of the rising necessity of rituals for mourning out of respect for the animal “ghosts of our fellow travelers.” It was a good speech, half improvised and all the more heartfelt for it.

Everyone paused and regarded the sunflower, which was due to be burnt as a pollinator pyre. It was torn and bent in a couple of places from being dinged against lampposts during our procession from the gallery to the park. An older man, greying beard bundled against the cold in a large scarf, exchanged a glance with Pearl and embarked on a more upbeat statement of what can be done, action that can be taken to support and protect pollinators in the U.K.

Before he got more than a couple of sentences in, Pearl stopped him. “I’m sorry, wait. I’m just not ready to move on yet. I’m not in the place for solutions yet. I’m too pissed off.”

She launched into a bitter litany of complaint. She’s as pissed off as someone might be who knew each bee personally, and watched them crumple and die. Her voice shook and she squeezed the tip of a sunflower petal to a sharp paper dart.

This RDLS gathering reminded me of my 1960s California hippie childhood, replete with countless self-fashioned ceremonies in all their messy, well-intentioned glory.

At this point, people pushed up their pink and black bat masks or wore them like scarves. The bumblebee goggles were removed. The procession through the streets had been a cheerful, bumpy rollick, but now the real face of grief and anger behind the absurdist theater was revealed.

One thing I’ve learned is that real spectacle starts where tamed emotion ends. At the pollinator procession, people aired their grievances, and all of the complaints began with anger. Isn’t anger at an original insult, at a profound loss, the very cornerstone of grief?

That might be why, in spite of being there as an observer, I heard my own voice rising with those around the sunflower in Brighton, lamenting a recent loss of my own: an old cherry grove lost to suburban development where I live in rural France, and the numerous birds’ nests in the unfinished house walls that had been smashed one day in early spring.

I only realized how furious I still was while standing there in Brighton. Angry at the impatient developers for not waiting a couple of weeks until the fledglings had flown, angry at the loss of the orchard, angry that I had fed groups of birds through several winters only to have them killed for the expediency of a construction schedule, angry at myself for not doing anything about it. There was a murmur of sad disgust as I finished my story, a moment of shared silence while I pictured the grove in its former glory, rich with birdsong, thick with bees, heavy with summer cherries. Then it was someone else’s turn.

When I was a kid in Golden Gate Park, I used to lie on the lawn, facing the sky, and feel myself as a part of the grass and trees, the park, the life all around me. There was no inkling then that any of it could ever disappear, or that I would be ill-equipped to confront the empty spaces that awaited.

Stanfield told me that learning about endangerment and species loss is how he got involved in the natural world in the first place. In this modern age of nature disconnect, where fewer and fewer people experience nature in a direct way, I suspect he’s not alone. Like Persephone Pearl and many others, Stanfield felt a fascination with certain extinct animals such as the thylacine.

The endearing strangeness of the thylacine draws people in with the seduction of a bygone era, like a crush on a long-dead movie star. Online conversations are replete with shared images and information, affectionate mash notes, and insider tidbits. What prods people into outrage is the injustice and recklessness of thylacine history, the government-sponsored bounty hunting and extirpation of a unique creature. This anger often piques an interest in species that are undergoing the extinction process today, or which have recently become extinct.

Most of the people I spoke with while discussing RDLS are open about experiencing depression. Creating rituals for dead species would seem to be the last thing that would alleviate the blues. But if the colossus of human impact on the environment weighs heavily on their minds and hearts, they say work with RDLS offers comfort.

A 2014 study by researchers Michael I. Norton and Francesca Gino at Harvard Business School on the value of mourning rituals in times of bereavement looked into the role that rituals played in building resilience when dealing with feelings of loss. A key discovery was that ritual — any ritual, private or public, traditional or personal — helped people cope with misfortune, as long as it was actually practiced. From burning the photos of a broken relationship to continuing the activities shared with a deceased spouse, those experiencing loss felt better by processing their grief. If tears and wishes can offer respite from sadness, it’s action that gives us control over grief.

Water, earth, and fire are the ritual standbys of humans, and at the pollinator procession, it was time for fire. The brisk wind (a fourth reliable element of ritual) had risen, so the large paper sunflower was broken into pieces that could be burned in a small fire pit rather than go up in a larger conflagration. The flower was big and took forever to burn down, the air was frigid, and people started to drift off with the ashes into the dark of night. That’s the problem with homemade rituals. It’s hard to tell when they end.

Maybe it was the harsh wind or the smoke from the burning sunflower effigy, but I shed a few tears among strangers in Brighton. Walking alone toward the English Channel afterwards, I was surprised to find that I had actually released some of my anger about the birds that had visited my garden annually, and now were gone.

Grieving is never going to get easier, but it can be shaped. It’s no surprise that the RDLS ceremony was a loose wobble of lament, humor, and ashes. It’s a new approach to a new phenomenon. Of course we should all be doing what we can to prevent habitat loss, to prevent extinction where we can, in whatever way we can. The extinction wave right now, unchecked by immediate human action on a vast scale, will affect and afflict everyone in unpredictable ways.

Pretend it’s not happening or acknowledge that it is, the wave is already crashing, and the horizons are changing. It’s time to figure out what kind of ritual raft will keep us afloat.

P.K. Read is a freelance writer and translator with an interdisciplinary background in history and environmental strategy. Her work has appeared in HuffPost, Litro, The Feminist Wire, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. She blogs at champagnewhisky.com.